When people hear "escort Russian," they often think of a woman walking beside a man at a gala or sitting across from him at dinner. But that’s only the surface. In Russia, the escort business isn’t just about giving company-it’s about emotional labor, cultural performance, and survival in a system where opportunities for women are tightly controlled. Many women enter this world not because they want to be seen as glamorous, but because rent is due, student loans are mounting, and traditional jobs pay less than minimum wage after taxes.

Some turn to platforms offering services like escorte girl c, not because they’re chasing luxury, but because they’re trying to build a life that doesn’t require begging for overtime or working two shifts. The demand isn’t just from wealthy foreigners or businessmen-it’s from lonely professionals, aging widowers, and even students who can’t afford therapy but need someone to talk to without judgment.

It’s Not About Sex-It’s About Presence

The biggest myth is that escort work equals prostitution. In Russia, the line is blurry legally, but socially, it’s sharper. Most clients aren’t looking for sexual encounters. They’re looking for someone who remembers their birthday, listens when they talk about their failed marriage, or wears a dress that makes them feel like they still matter. One woman in Moscow, who goes by the name Elena, told me she once spent three hours walking through a cemetery with a client who just wanted to talk to his late wife out loud. She didn’t charge extra. She brought tissues.

This isn’t rare. A 2024 survey by a Moscow-based NGO found that 68% of clients in regulated escort services explicitly stated they wanted "emotional companionship," not physical intimacy. The women who do this work often train themselves in psychology, etiquette, and even basic first aid-not because it’s part of the job description, but because they’ve learned that a client’s real need isn’t a date. It’s validation.

The Hidden Rules of the Russian Escort Scene

There are no official licenses, no unions, no HR departments. But there are rules. Strong ones. If you show up late, you’re fired. If you argue with a client about their behavior, you’re blacklisted. If you cry during a session, you’re marked as "unstable"-and that’s worse than being fired. These women learn to smile on command, to laugh at jokes they don’t find funny, to remember the names of children they’ve never met.

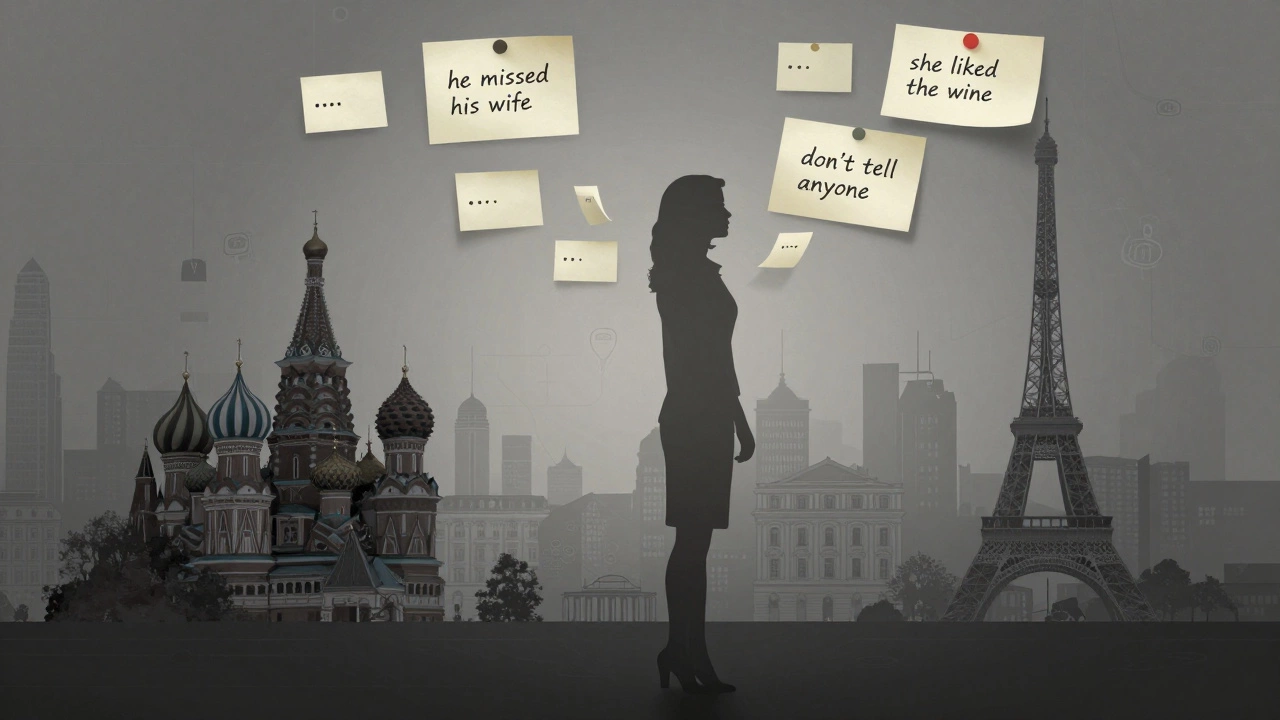

Many use code names. Some have fake social media profiles just to separate their work identity from their real life. Others keep journals-not to record client details, but to remind themselves they’re still human. One woman in St. Petersburg wrote in her diary: "Today I pretended to love his cat. I didn’t. But I gave him the illusion. That’s the job. Not the sex. The illusion."

There’s also a hierarchy. Entry-level escorts might earn 5,000 rubles ($55) for a two-hour dinner. Mid-tier make 15,000-25,000 rubles ($165-275) for weekend trips. Top-tier women, often multilingual and educated, can command 100,000 rubles ($1,100) or more for week-long stays abroad. They’re the ones who get invited to art openings, diplomatic receptions, or private concerts. They’re the ones who get asked to pose for magazines-not as models, but as "companions of influential men."

Why Paris Is a Magnet for Russian Escorts

Paris isn’t just romantic. It’s anonymous. In a city where 40% of residents are foreign-born, blending in is easy. Russian women who work as escorts in Paris often say it’s the only place they feel safe being themselves. The French legal system doesn’t criminalize escorting as long as it’s consensual and doesn’t involve brothels. That’s why you’ll find Russian women working under the name "escort parijs"-not because they’re trying to be exotic, but because it’s the easiest way to be found by clients who speak English or Russian.

Many of them live in the 15th or 16th arrondissements, where rent is lower and the metro connects them to the major hotels. They don’t advertise on street corners. They use encrypted apps, private forums, and referrals. Some work with agencies that handle scheduling, translation, and security. Others work solo, using LinkedIn profiles to appear legitimate. One woman I spoke with, who goes by "Anna," said she lists herself as a "cultural consultant" on her profile. Her real job? Taking clients to museums, explaining Russian literature over wine, and pretending she’s not exhausted.

And then there are the women who call themselves "scorts en paris"-a spelling mistake, yes, but one that’s become a quiet brand. It’s not about being trendy. It’s about being searchable. Google doesn’t care about grammar. It cares about traffic. And in Paris, that misspelling gets them more clients than the polished versions.

The Cost of Being Seen

Every escort in Russia knows the risks. The police don’t arrest them often, but they do show up at their apartments. Landlords kick them out. Family disowns them. One woman in Kazan lost her job as a schoolteacher after a client’s wife found her Instagram. The school board called it "moral corruption." She now works in a call center, but she still gets calls from old clients asking if she’s "still doing the work." She says yes. Sometimes, she says no. Either way, she doesn’t hang up.

The emotional toll is heavier than the physical one. Many suffer from dissociation-feeling like they’re watching themselves from outside their body. Some develop chronic insomnia. Others stop watching romantic movies. A few start therapy. Most don’t. It’s too expensive. Too stigmatized. Too hard to explain to a stranger that you’re not broken-you’re just doing a job no one else wants to admit exists.

What Happens When They Leave?

Some women leave after a year. Others stay for a decade. Those who leave often struggle to rebuild. No one hires a former escort for a corporate job. No university accepts her application without asking why she took off two years. Even in tech, where skills matter more than resumes, her name comes up in background checks-and then the silence follows.

But not all leave broken. Some start blogs. Others open small cafés in provincial towns, where no one knows their past. A few become advocates, quietly helping new women navigate the system, teaching them how to screen clients, how to say no, how to keep receipts so they can prove income for loans. One woman in Yekaterinburg now runs a nonprofit that teaches financial literacy to women in the industry. Her slogan? "You’re not selling yourself. You’re selling your time. And your time is worth more than you think."

Why This Matters

This isn’t about morality. It’s about economics. When a woman in Russia has to choose between paying for her child’s medicine or going on a client’s weekend trip, the decision isn’t glamorous-it’s survival. The escort business isn’t a secret underground world. It’s a shadow economy that exists because the official economy failed too many women.

And yet, no one talks about it in policy meetings. No politician mentions it in speeches. No charity runs a campaign for it. The women who do this work aren’t victims. They’re not criminals. They’re workers. With contracts, schedules, and clients who expect professionalism. They just don’t get the same rights as waitresses, nurses, or delivery drivers.

Maybe the real question isn’t why women become escorts. It’s why society refuses to see them as anything but a stereotype.